9 Weeks 5 Days Baby Moves Some Days but Not Others

- Enquiry article

- Open Access

- Published:

Fetal movement in tardily pregnancy – a content analysis of women'southward experiences of how their unborn infant moved less or differently

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume xvi, Article number:127 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Pregnant women sometimes worry about their unborn baby'south health, frequently due to decreased fetal movements. The aim of this study was to examine how women, who consulted wellness intendance due to decreased fetal movements, draw how the baby had moved less or differently.

Methods

Women were recruited from all seven delivery wards in Stockholm, Sweden, during one/ane – 31/12 2014. The women completed a questionnaire after information technology was verified that the pregnancy was feasible. A modified content assay was used to analyse 876 questionnaires with the women's responses to, "Try to depict how your baby has moved less or had changes in movement".

Results

Iv categories and half dozen subcategories were identified: "Frequency" (decreased frequency, absenteeism of kicks and motility), "Intensity" (weaker fetal movements, indistinct fetal movements), "Character" (changed blueprint of movements, slower movements) and "Duration". In addition to the responses categorised in accord with the question, the women also mentioned how they had tried to stimulate the fetus to move and that they had difficulty in distinguishing fetal movements from contractions. Farther, they described worry due to incidents related to inverse design of fetal movements.

Conclusion

Women reported changes in fetal move concerning frequency, intensity, grapheme and duration. The challenge from a clinical perspective is to inform pregnant women about fetal movements with the goal of minimizing unnecessary consultations whilst at the same time diminishing the length of pre-infirmary filibuster if the fetus is at run a risk of fetal compromise.

Trial registration

Not applicable.

Groundwork

It is widely acknowledged that a pattern of regular movements is associated with fetal wellbeing [1]. Fetal movements tin be divers as any discrete kick, flutter, swish or ringlet and are normally first perceived by the mother between 18 and 20 weeks of gestation [2]. The frequency of fetal movements reaches a plateau in gestational calendar week 32 and stays at that level until birth [3]. There is unremarkably a variation in fetal movements with a wide range in the number of movements per 60 minutes [4]. The movements are commonly absent during sleep and occur regularly throughout the twenty-four hour period and night, normally lasting for 20–40 min. The sleep cycles rarely exceed 90 min in the normal and healthy fetus [5]. Although the movement pattern of the individual fetus is unique, it is general noesis that decreased fetal movement is associated with adverse outcome, including stillbirth [6].

The character of the movements changes when the pregnancy approaches commitment due to limited space in the uterus, but the frequency and intensity will not normally decrease [three]. In an interview study, 40 term pregnant women with an outcome of a healthy infant described fetal movements during the past week. Almost all experienced fetal movements equally "stiff and powerful". Half of the women besides described the movements as "large" (involving the whole body of the fetus). Another common description was "slow" as in "boring move" and "stretching" or "turning". Some of the women stated that they were surprised how powerfully the fetus moved [7].

Several maternal factors may impair the ability to recognize fetal movement [8]. Amniotic fluid book [9], fetal position [10], having an inductive placenta [10, 11], smoking, beingness overweight [6] and nulliparity [half dozen, 12] have been reported as such factors. Maternal factors which may enhance the ability to recognize motion are the opportunity to focus on the fetus and the absence of distracting noises [thirteen]. Almost 50 % of the pregnant women in a study from Norway were sometimes worried virtually decreased fetal movements [fourteen]. In a review article, it was found that betwixt iv and fifteen pct of significant women consult health care because of a decrease in fetal motion in the third trimester [1]. The aim of the present report was to examine how women, who consulted health care due to decreased fetal movements after gestational week 28, describe how the baby had moved less or differently.

Methods

Settings and participants

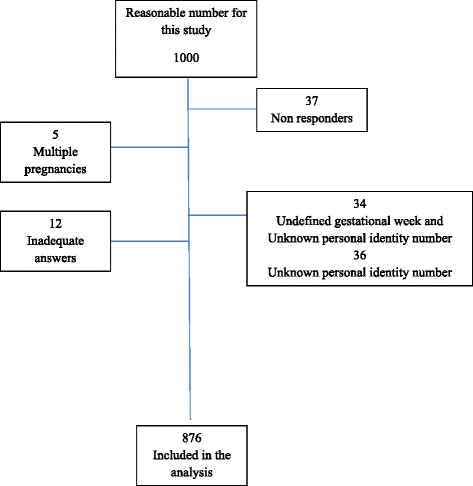

Women were recruited from all seven delivery wards in Stockholm, Sweden from 1st January to 31st December 2014, and were asked to consummate a questionnaire. The inclusion criteria were women in gestational week 28 or more who consulted health care due to concerns over decreased fetal movements, with the ability to understand Swedish or English language and a normal cardiotocography (CTG). Non responders, inadequate answers, multiple pregnancies, undefined gestational calendar week and unknown personal identity number were exclusion criteria (Fig. ane). In total, 3555 questionnaires were completed during the data drove period. Information collection was in progress while the beginning grand questionnaires were analysed. Twenty-viii women completed ii questionnaires and 3 women filled in iii questionnaires; they consulted health care more than once during the data collection period due to concerns over decreased fetal movements. Of the women, 672 (76.7 %) were aged 20–35 years, 582 (66.four %) had a college or university level of instruction and 650 (74.2 %) of the women were born in Sweden (Table 1). All women gave birth to a alive child.

Menstruum nautical chart

Information collection

The questionnaire used in the study was adult from a web survey, an interview study [7, fifteen] and clinical experience. The questionnaire was face-to-face validated with ten women who consulted health care due to reduced fetal movements, not included in the study. The concluding version of the questionnaire included a total of 22 questions with multiple-choice or open-ended response alternatives (Additional file 1). This study comprises the women'southward responses to the asking: "Effort to describe how your babe has moved less or had changes in movement". The women were asked to describe their experiences in the space provided simply could as well, if necessary, go along on the back of the questionnaire.

Analysis

The women's descriptions (northward = 876) of how their unborn baby had moved less or differently were analysed using a modified content assay [sixteen]. The material consisted of concise descriptions of movements, which were used without editing. The analysis was performed in three steps. Firstly, all the answers were read and re-read iii times to gain a sense of content in the data. Codes were and then revealed in accordance with Malterud. Every quotation was read and sorted into codes. In the second phase of the assay the textile was organized. Units, the quotations, with the aforementioned lawmaking were divided into defined chief categories and categories. When advisable the categories were divided into subcategories [17] The quotations could be placed in more one category. Nevertheless, each statement was only placed in 1 subcategory. During the whole process the findings were continually discussed in the research group in social club to achieve agreement. To validate the results, a sample of l quotations was randomly selected and re-analysed from the beginning of the analysis procedure. Later on consensus had been reached some of the quotations were transferred to other subcategories and 3 quotations were accounted irrelevant and removed. Those carrying out the analysis did not know the gestational week.

Results

Four primary categories and six subcategories were identified: "Frequency" (decreased frequency, absence of kicks and movement), "Intensity" (weaker fetal movements, indistinct fetal movements), "Grapheme" (changed pattern of movements, slower movements) and "Duration". The number in each category and subcategory every bit well as an presentation of the figures for women seeking health intendance in gestational week 28–32, gestational week 33–36 and during gestational week 37+, are shown in Table 2.

Frequency

The most commonly experienced divergence of fetal movements concerned frequency, which was described in 746 (85 %) of the questionnaires. This category was divided into ii subcategories; "Decreased frequency" and "Absence of kicks and move".

Decreased frequency of fetal motion

This subcategory comprises 609 (69 %) statements. These statements referred to movements becoming less frequent and indicating to the women a by and large decreased liveliness in the fetus. The movements were described with words similar, "a few", "seldom", "less frequent", "not as many" and "decreased activity".

"Less frequent during the day"

"From existence very active and kicking a lot to very few movements during some days"

Absenteeism of kicks and move

Among the answers about the frequency of fetal movements, 137 (16 %) statements were virtually not feeling any motion at all.

"I haven't felt any kicking for most 12 hours"

"Have not felt any movement during the whole day"

Intensity

A total of 343 (39 %) responses were perceptions that the movements had altered in intensity. Two subcategories were formed: "Weaker movements" and "Indistinct movements".

Weaker fetal movements

This subcategory comprised 277 (32 %) statements. Words oftentimes used were: "Weaker", "Softer", "Less abrupt" and "With less ability".

"From obvious, stiff movements and nudging to feathery tickling a few times a day"

"… The movements of the baby felt weaker the few times I have felt my baby"

Indistinct fetal movements

Sixty-six (eight %) statements barbarous into this subcategory. Some women were uncertain as to whether they felt anything at all but thought they could imagine movements.

"…The only matter I felt was non-specific movements deep inside my tummy…"

"Take previously felt apparent kicks which tin can be both felt and seen distinctly. Since yesterday evening only small occasionally twisting movements"

Character

This category comprised 252 (29 %) statements describing experiences of the fetal movements irresolute in character. The category revealed two subcategories: "Changed pattern of movements" and "Slower movements".

Changed pattern of movements

This subcategory comprised 141 (sixteen %) statements. The women described the fetal movements as having changed in pattern and decreased in activeness.

"Not the same pattern of movements as before and not active at the aforementioned time"

"The baby has non moved at the times that she had moved earlier, post-obit the design that she had previously. This has been going on for about 2 days. When she has moved, the movements felt weaker the by 2 days compared to earlier."

Slower movements

This subcategory included 111 (13 %) statements. When talking almost the movements women used words such as: "sluggish", "indolent", "tiresome and sweeping".

"Calmer more tired movements as if it were tired…"

"Slow and smoother movements"

Duration

Thirty-eight (four %) were included in this category. Women reported that the periods of movement had go shorter and had been reduced from several kicks in a row to occasional ones. Even so, the frequency of how often the baby had moved had not decreased.

"… the periods when it has moved have been shorter"

"No more lively periods."

Differences according to gestational age

Women in gestational weeks 33–36 experienced changes more oft than women at term regarding the category Frequency (92 % vs. 81 %), the subcategory Decreased frequency (75 % vs. 67 %), and the category Intensity (42 % vs. 35 %). Compared to women at term, those in gestational weeks 28–32 expressed changes to a lesser extent within the category Character and the subcategory Slower movements (5 % vs. 15 %) (Table 2).

4 percent, 32/876, of the total number of women in this study only stated a change in the character of the movements, not included in whatsoever other category. The distribution regarding length of pregnancy was; gestational calendar week 28–32, 1/190 (0.5 %), 33–36, 1/263 (0.4 %) and gestational weeks 37+, 30/423 (7 %). At that place were no statistically significant differences in the other categories (Not in table).

In addition to the responses categorised in accord with the question, the women also mentioned how they had tried to stimulate the fetus to movement and that they had difficulty in distinguishing fetal movements from contractions. Further, they described worry due to incidents related to changed pattern of fetal movements.

Stimulation due to less movement

Nosotros identified 146 (17 %) statements most trying to provoke move by triggering the fetus. Most of the women reported that they did this when non having felt movements for a while. When they did not succeed they consulted health care. The methods used to trigger movements were to pull, nudge or push on the tum, stimulate with light or racket, accept a shower or bath or to beverage common cold, sweet drinks. Others said that they had various positions they used to feel the infant more distinctly. Some women described not feeling movements without stimulating the baby.

"No pushes" back when I am pulling on the tummy, no reaction when drinking a glass of lemonade. Otherwise he has been quite agile and you have been able to encounter my tummy moving"

"Even if I touch my tummy, eat, drink, in that location is not much difference. He is moving considerably less"

Hard to distinguish fetal movements from contractions

The women stated that the fetal movements ceased or inverse in relation to contractions or that information technology was difficult to distinguish movements from contractions. Some women also described that the movements decreased in relation to contractions, pain in the tummy or the dorsum. We identified 40 statements (v %) concerning difficulties in distinguishing fetal movements from contractions.

"Not felt any movements since the contractions became more intensive"

"Information technology has been more than hard to perceive movements. Difficult to distinguish movements from contractions… previously the movements have been very distinct"

Worry due to incidents related to inverse pattern of fetal movements

We identified 25 (3 %) statements about external factors, such equally the woman was ill and perceived less fetal move. Six women stated that they consulted health care due to pain in relation to inverse patterns of fetal move. 2 statements referred to the woman having taken a fall and wanting to be reassured that the fetus had not been damaged. Other reasons related to increased worry were: post maturity, post-obit an expelled mucus plug, an external cephalic version attempt, rupture of the membranes and previous stillbirth in the same gestational week.

"Used to motility a lot during both day and night. Have been ill with fever for three days and then in that location have been movements iv–five times every twenty-iv hours"

"Not equally oft equally earlier but I nevertheless experience him daily. We're extremely worried as we lost our first child in gestational week 33 in utero so information technology may exist imagination"

Discussion

We are not aware of any studies that take categorized how women describe the changes they have perceived apropos fetal movements when they seek wellness care due to worry nigh their unborn babe.

Women who consulted health care due to decrease fetal movements described changes in frequency, intensity, character and duration of the movements. However, all women in this written report were reassured afterward an exam of their unborn infant. In Norway, equally many equally 51 % of women reported that they were concerned about decreased fetal movements once or more in pregnancy [14]. In different populations, between iv and xv % consulted health care facilities because of decreased fetal movements in the tertiary trimester [i]. There are several factors which may impair the ability to recognize fetal movements [8]. However, we have no data apropos amniotic fluid book, fetal position, placenta position, smoking, overweight and nulliparity among the women participating in this study. These factors may explicate some of the women's perceptions of decreased fetal movements. Also, the plateau in gestational calendar week 32 [3] may be perceived as a decrease. In a study by Sheikh and colleagues (2014), 729 women counted and registered fetal movements for one hr three times per 24-hour interval. Eight percentage of the pregnant women in the tertiary trimester, who in the end gave birth to a healthy child, experienced reduced fetal movements. Further, the researchers establish that among women who consulted health care for reduced fetal movements just later gave birth to a healthy child, more of them were working than those who did not perceive reduced fetal movements [18]. Nosotros do not have data every bit to work status amid the women participating in our study.

Placental dysfunction is one principal reason for decreased fetal movements in late pregnancy [19]. It is thus important for the pregnant women to recognize the pattern of motion. A change may be a sign of asphyxia due to the redistribution of the circulation which gives priority to the brain over peripheral parts [20]. All fetuses in the present report were examined and no symptoms of asphyxia or placental dysfunction were identified at the time when the woman consulted wellness intendance. The women'due south worry nearly their unborn baby's health due to decreased fetal movements in this report did not consequence in a diagnosis or actions to induce the delivery.

Our results indicate that some women at term seek wellness care due simply to a change in the character of the fetal movements. Although these women were asked to describe how their baby had moved less or differently, they did not mention a decrease in frequency in the fetal movements or a change in intensity. Tiresome, equally in slow movement, stretching and turning, are descriptions of the character of fetal movements used by women in full term pregnancy, pregnancies that resulted in a healthy child [7]. The women in our report who consulted health intendance simply due to a alter in the character of the movements and non considering of contradistinct frequency and intensity might not have been enlightened of normal changes in the fetal motion patterns in belatedly pregnancy. The changes they reported as different can be physiological due to express space in the uterus at term [3]. There is no routine in Swedish antenatal wellness care for giving information about fetal movements only women are recommended to consult wellness care if they experience decreased fetal movements [21]. However, pregnant women ask for information nigh fetal movements in general and for data nigh the number and type of fetal movements they tin can wait, as well as how the movements are supposed to change over time in pregnancy [22].

There were no stillbirths among the women in this study. Thus, nosotros tin merely speculate that it is possible that women who consult health intendance due to decreased or changed patterns of fetal motion may be enlightened of the importance of detecting fetuses at risk every bit early as possible. Detection of decreased fetal movements can improve the outcome and reduce delay in consulting health intendance [23, 24]. Further, the fetuses in this report who could be at risk were examined and risk factors such as placental abruptions, growth retardation or malformations [25] may accept been detected. The chief reason for consulting health care due to decreased fetal movements is worry about the health of the baby [xiv]. None of the women in our report consulted wellness intendance without cause, but their worry was obviously unfounded from a medical perspective in the short term.

Strengths and limitations

Women in this study had a normal CTG before they completed the questionnaire. Still, aside from no stillbirths amid the participating women, we have no data regarding the health status of the baby after birth. This is a major limitation of the study. In that location is also only sparse information most the women's' sociodemographic background.

One strength of the study is the large number of participants. Another strength is that all delivery wards in Stockholm participated in the study. However, all women came from the upper-case letter urban center in Sweden where women in generally are older and well educated compared with women outside the capital. Farther, the number of those who declined to participate and their reasons for doing so are not known.

The diction of the asking, "Try to describe how your infant has moved less or had changes in motility" might accept influenced the responders to use the words "decreased" and "differently" in their descriptions of their experiences. The results may have yielded fifty-fifty more than if the initial asking had been broader or more open up, for case, "Attempt to draw how your babe has moved". However, the context in which the women completed the questionnaire was ane of already perceived decreased fetal movements.

Clinical implications

Increased knowledge near the normal changes in the fetal movement patterns in late pregnancy can be one style to lessen the number of visits to obstetric clinics from women over concerns that turn out to be unnecessary from a medical perspective. The challenge from a clinical perspective is to inform and advise pregnant women about fetal movements with the goal of diminishing the length of pre-hospital filibuster if the fetus is at chance and at the aforementioned time reduce worry leading to unnecessary consultation. Reducing the pre-hospital delay when the intrauterine environment is a threat to the unborn baby'due south life will provide a window of opportunity to save a greater number of children from expiry or compromised health. Further, fewer visits to obstetric clinics, over concern that turns out to be unnecessary from a medical perspective, will have wellness economic benefits. Earlier giving definitive advice that tin can reduce unnecessary controls at the stop of the pregnancy, distinct differences must be identified regarding how women who lost their child intrauterine or have given birth to a hypoxic or anaemic child, report the changes in grapheme of movements equally simply symptoms when they seek treat decreased fetal movements. Future studies are needed.

Conclusions

Women reported changes in fetal motion concerning frequency, intensity, character and duration; they described decreased, absence, weaker, slower and changed blueprint of the movements.

References

-

Froen JF. A kick from within--fetal movement counting and the cancelled progress in antenatal care. J Perinat Med. 2004;32(1):xiii–24. doi:10.1515/JPM.2004.003.

-

Neldam S. Fetal movements as an indicator of fetal wellbeing. Lancet. 1980;1(8180):1222–4.

-

RCOG. Green-top guideline No.57: reduced fetal movements. London: Majestic College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2011. http://world wide web.rcog.org.uk/womens-wellness/clinical-guidance/reduced-fetal-movementsgreen-pinnacle-57. Accessed 17 May 2016.

-

Nowlan NC. Biomechanics of foetal movement. Eur Cell Mater. 2015;29:i–21. discussion.

-

Patrick J, Campbell K, Carmichael L, Natale R, Richardson B. Patterns of gross fetal body movements over 24-60 minutes observation intervals during the terminal 10 weeks of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142(4):363–71.

-

Holm Tveit JV, Saastad Eastward, Stray-Pedersen B, Bordahl PE, Froen JF. Maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes in women presenting with decreased fetal movements in late pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(12):1345–51. doi:10.3109/00016340903348375.

-

Radestad I, Lindgren H. Women'due south perceptions of fetal movements in total-term pregnancy. Sex activity Reprod Healthc. 2012;3(iii):113–6. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2012.06.001.

-

Hijazi ZR, E CE. Factors affecting maternal perception of fetal movement. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64(7):489–97. doi:10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181a8237a. quiz 99.

-

Ahn MO, Phelan JP, Smith CV, Jacobs N, Rutherford SE. Antepartum fetal surveillance in the patient with decreased fetal movement. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(4 Pt 1):860–4.

-

Fisher ML. Reduced fetal movements: a research-based project. Br J Midwifery. 1999;7:733–7.

-

Fried AM. Distribution of the bulk of the normal placenta. Review and classification of 800 cases by ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;132(six):675–eighty.

-

Mohr Sasson A, Tsur A, Kalter A, Weissmann Brenner A, Gindes Fifty, Weisz B. Reduced fetal movement: factors affecting maternal perception. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015:1–4. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1047335.

-

Johnson TR. Maternal perception and Doppler detection of fetal movement. Clin Perinatol. 1994;21(4):765–77.

-

Saastad Eastward, Ahlborg T, Froen JF. Depression maternal awareness of fetal movement is associated with small-scale for gestational age infants. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(4):345–52. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.03.001.

-

Linde A, Pettersson Thou, Radestad I. Women's experiences of fetal movements before the confirmation of fetal death--contractions misinterpreted as fetal movement. Birth. 2015;42(two):189–94. doi:10.1111/birt.12151.

-

Malterud K. Shared understanding of the qualitative research procedure. Guidelines for the medical researcher. Fam Pract. 1993;10(2):201–half dozen.

-

Malterud M. Kvalitativa metoder i medicinsk forskning. tertiary ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2014.

-

Sheikh Thou, Hantoushzadeh Southward, Shariat M. Maternal perception of decreased fetal movements from maternal and fetal perspectives, a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:286. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-xiv-286.

-

Scala C, Bhide A, Familiari A, Pagani G, Khalil A, Papageorghiou A, et al. Number of episodes of reduced fetal movement at term: association with agin perinatal result. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.015.

-

Jensen A, Garnier Y, Berger R. Dynamics of fetal circulatory responses to hypoxia and asphyxia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;84(2):155–72.

-

SFOG. In: Lars-Åke G, editor. Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och Reproduktiv Hälsa. Stockholm: Svensk Förening för Obstetrik och Gynekologi; 2008. p. 52.

-

McArdle A, Flenady V, Toohill J, Gamble J, Creedy D. How meaning women learn virtually foetal movements: sources and preferences for data. Women Birth. 2015;28(one):54–9. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2014.ten.002.

-

Froen JF, Arnestad Thou, Frey Thousand, Vege A, Saugstad OD, Stray-Pedersen B. Risk factors for sudden intrauterine unexplained death: epidemiologic characteristics of singleton cases in Oslo, Norway, 1986–1995. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(iv):694–702.

-

Grant A, Elbourne D, Valentin L, Alexander S. Routine formal fetal movement counting and risk of antepartum tardily expiry in normally formed singletons. Lancet. 1989;2(8659):345–9.

-

Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Froen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, et al. Major take a chance factors for stillbirth in loftier-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331–xl. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7.

Funding

The Footling Kid's Foundation, Sophiahemmet Foundation, The Swedish National Baby Foundation and Capo'south Research Foundation funded this study.

Availability of data and materials

The data will non be fabricated available in order to protect the participant'south identity.

Authors' contributions

AL, KP and IR participated in the design of the study. AL, SG and IR performed the qualitative analyses. SH and EN carried out the first and main part of the analysis. KP contributed to the discussion of the analysis. AL, SG, KP and IR drafted all versions of the manuscript. AL, SG, KP, SH, EN and IR commented on the draft. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The women gave consent to participate and permission to access supporting information when receiving information nigh the study. The data will not be made available in order to protect the participant'southward identity. The written report was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm: DNR: 2013/1077-31/three.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Boosted file

Rights and permissions

Open up Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite advisable credit to the original writer(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this commodity

Linde, A., Georgsson, South., Pettersson, K. et al. Fetal motion in late pregnancy – a content analysis of women's experiences of how their unborn baby moved less or differently. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 127 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0922-z

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12884-016-0922-z

Keywords

- Pregnancy

- Fetal motility

- Decreased fetal movements

- Content assay

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-016-0922-z

0 Response to "9 Weeks 5 Days Baby Moves Some Days but Not Others"

Post a Comment